Training in strategic analysis through practice: an open source intelligence case study designed by students at Albert School

With the proliferation of data available online, knowing how to collect, qualify, and interpret open information has become a major strategic challenge for businesses, public institutions, and international organizations. Open source intelligence (OSINT) has thus emerged as a key skill for analyzing complex environments, anticipating risks, and informing decision-making.

It is in this context that two Albert School students, Baptiste and Alexandre, have designed a teaching case study devoted to OSINT applied to risk management and strategy. Far from a purely theoretical approach, this program offers students the opportunity to engage in an analytical process similar to that of practitioners: identifying relevant open sources, questioning the reliability of information, cross-referencing data, and structuring strategic reasoning based on elements that are sometimes fragmentary or uncertain.

This student initiative illustrates the pedagogy promoted by the joint Mines Paris – PSL x Albert School programs, based on learning by doing and the production of knowledge by the students themselves. By making OSINT a subject of study and an educational tool, this case study addresses key contemporary issues—information quality, cognitive biases, decision-making in uncertain environments—while developing hybrid skills at the intersection of data, social sciences, and management.

Baptiste (left) and Alexandre (right)

The case study written by the students is presented in its entirety below.

Open Source Intelligence (OSINT), or the collection and analysis of information from so-called open sources (social networks, media, public records, corporate and commercial websites, open data, etc.), is now an essential strategic tool for public and private actors. Its scope of application is vast and can be used for intelligence, economic monitoring, risk prevention, and even territorial planning.

OSINT now accounts for 80 to 90% of the information that can be used in operational contexts, and its market is estimated at $5 billion with an average annual growth rate of 25%, reaching $60 billion by 2033. What’s more, in business applications, the use of OSINT delivers measurable benefits: +55% analytical productivity and 268% ROI over three years, enabling cost reduction, risk reduction, competitive advantage, and strategic support.

However, what matters is not only what the open data says, but how it structures reasoning or a pattern.

The goal is therefore to align this reasoning with business experience and use it to make technical decisions that can be applied to planning, prevention, and decision-making. We will address each of these issues using the example of Business Deep Dive (practical cases), organized by Albert School x Mines Paris, each lasting three weeks.

Planning public action means first deciding where and how to act in order to maximize the impact of government resources. Long based on experience and intuition, these approaches can now rely on OSINT.

In this case, we were able to use OSINT to identify priority areas for the establishment of youth-focused structures for the Ministry of Defense, the National Service and Youth Centers (CSNJ), with the main objective of making these facilities more accessible, better distributed, and more consistent with the real needs of the regions.

Given this need, a model must be able to approximate real needs as closely as possible. Therefore, we must take into account institutional, socio-economic, and spatial data, as well as their scope of interest. We must therefore cross-reference various public data sources, such as INSEE, Data.gouv.fr, similar facility websites, and Google Maps, in order to create a common geospatial database.

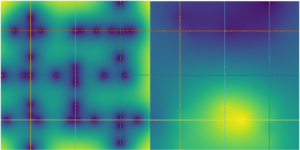

In order to determine the ideal locations for CSNJ implementations as accurately as possible, we must gradually segment the territory by dividing the geographical space into homogeneous subsets, taking into account population density, socio-economic indicators, and proximity to existing infrastructure.

The algorithm, written in C, is an advanced adaptation of the KD-Tree (a structure initially designed to speed up searches in a multidimensional space). In its initial version, the KD-Tree divides the space into sub-areas along a chosen axis in order to efficiently organize points in a geometric space. In this specific case, the tree is used to understand the structure of the territory, weight areas of interest, and reveal the regions where public action is most relevant.

Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) now offers considerable potential for risk management and prevention. By exploiting freely accessible public data sources, whether government open data, accident databases, socio-economic indicators, or transport networks, it is possible to build predictive models to understand risk at a level of granularity that was previously difficult to achieve. In the insurance sector, risk assessment methods remain largely aggregated at the regional or socio-demographic level.

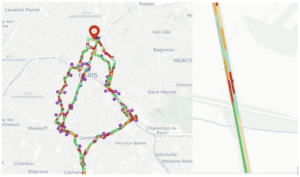

In particular, the cross-referencing of field data (from BAAC files: Bulletins d’Analyse des Accidents Corporels sur 10 ans, or 10-year bulletins analyzing physical accidents) with INSEE territorial data and open infrastructure (roads, transportation, density, lighting, etc.). This makes it possible to establish a contextual risk index for each road segment, expressed on a scale of 0 to 100. This score reflects the weighted probability of a serious or fatal accident, adjusted for each environmental condition and each type of vehicle. This OSINT model makes it possible to spatially project the actual risk on a given route, city, or even neighborhood. It thus becomes possible to measure a driver’s accident risk, not based on their profile, but on their actual routes.

The engine is based on a set of geospatial and statistical processes that associate each road segment with a risk calculated from historical accidents.

Each accident is georeferenced, normalized (correction of latitudes/longitudes, transformation into Lambert 2154 projection) and enriched with metadata: Maximum authorized speed (VMA), Road category (catr): national, departmental, municipal, Traffic and surface (circ, surf), Vehicle category (catv), Severity of injury (grav): fatal, serious, minor. These attributes are then combined into two multipliers: for location conditions and for vehicle type. Each accident point is thus given a weighted adjusted severity value.

Accident points are then linked to road segments divided every 100 to 250 meters. The code uses a KDTree for this purpose, which allows the risk to be spatialized, enabling each accident to be assigned to the nearest segment within a radius of 22 m to 28 m. A Gaussian spatial smoothing is then applied (a method that partially neutralizes the effects of overly small samples) where each segment is compared to its neighbors within a radius of 80 to 120 m, with exponential weighting and an attenuation factor (all of which is equivalent to a geographic moving average and brings the method closer to geostatistical kriging—for more information: How Kriging Works—ArcGIS Pro).

In order to obtain a usable algorithm and thus enable interregional comparison, a normalized logarithmic scale is used, allowing the most dangerous segments or patterns to obtain higher scores (high curvature, intersections, fast-moving suburban areas, etc.).

However, this model would not be close to observable reality if it did not allow alternative routes between two points to be simulated, by closely reproducing the logic of the A* algorithm, incorporating time and route probability constraints, where each route k is associated with a probability weighted by the difference in distance and time, thus expressing the overall risk expectation, the trade-off between time and distance using a Monte Carlo simulation (MCS).

Deciding in an environment saturated with information and subject to constant systemic shocks requires the ability to prioritize, anticipate, and rationalize complexity. Alternative strategic intelligence aims precisely at this: understanding before predicting, predicting before acting.

We can find this logic in several fields, particularly finance, with asset management as an example.

The objective could therefore be to mimic the cognitive process of an investment committee within a management company, relying not only on financial data, but also on a set of weak behavioral signals using OSINT.

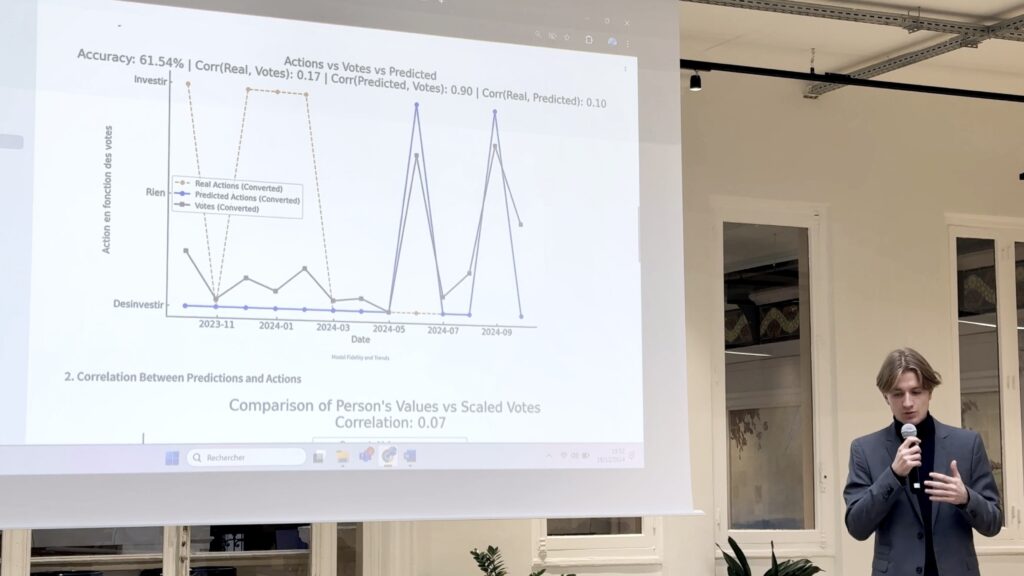

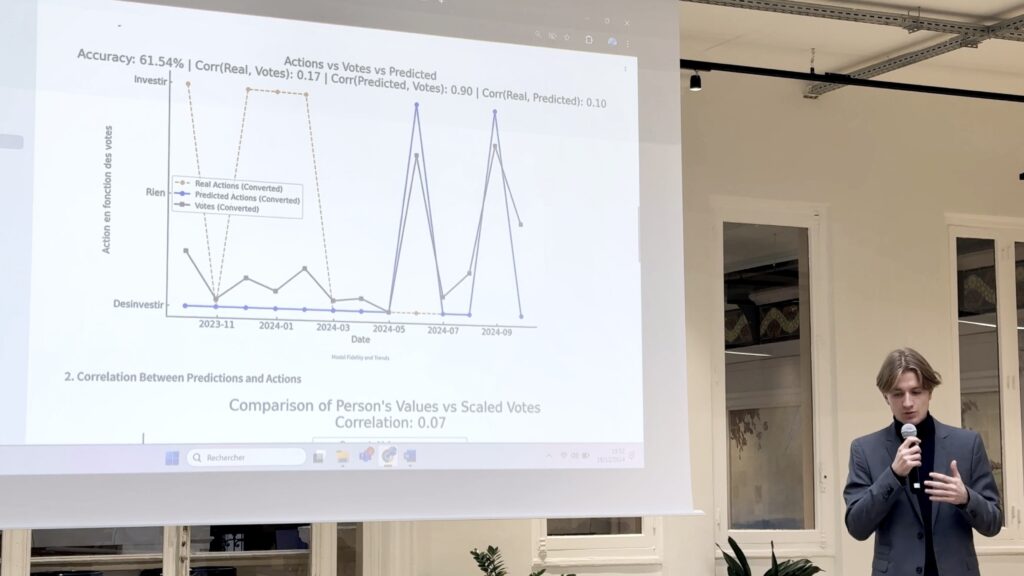

More specifically, it is an experimental model of explainable algorithmic reasoning, capable of reproducing the actual decisions of professionals with 68.6% accuracy: “Buy,” “Hold,” or “Sell.”

This approach goes beyond simple machine learning. It is an attempt to model human rationality and its biases using open data, in order to equip decision-makers with strategic intelligence that complements, rather than replaces, their own judgment.

Alternative strategic intelligence differs from traditional monitoring or data science systems in three ways:

In this model, decisions are not based solely on statistical correlation; they emerge from cognitive consistency between economic signals, public emotions, and decision-making personality.

The algorithm does not seek to “be right” about the market, but to understand how and why a rational human being in a given context would decide to act in a certain way.

The system integrates five classes of data, combining market data, media events, behavioral indicators, macroeconomic signals, and data from open sources such as GDELT and LinkedIn.

Each source is time-stamped, normalized, and projected into a multidimensional vector space where economic rationality and emotional signals coexist.

The model’s architecture is deployed in four main layers, forming a coherent chain: perception, inference, deliberation, decision.

A specialized BERT model extracts psychological traits (based on the Big Five theory, among others) and emotional tone indicators (positivity, anxiety, lexical intensity).

Each manager is then represented by a behavioral vector pᵢ ∈ ℝ⁴, measuring their cognitive profile (Introversion, Intuition, Thinking, Judgment).

Based on these vectors, the system estimates the probability of behavioral bias in the face of a market shock.

The expected utility of a decision a at a given moment t therefore depends not only on economic signals s(t), but also on the personality p of the decision-maker and the informational context c(t):

This formal calculation translates into practice an individual’s propensity to act according to their psychological structure and cognitive environment.

The model’s major originality lies in the simulation of a virtual committee: several “virtual” agents debate, each with a different personality profile.

The logic follows a Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS), where each node represents a strategic alternative (buy, hold, sell) and where the final decision results from a weighted propagation of utilities.

We put this method into practice and adapted it in less than three weeks during a practical case study, and the results are remarkable:

| Indicator Observed | Value | Interpretation |

| Overall accuracy | 68,6 % | The model reproduces more than two-thirds of actual decisions. |

| Recall on sell signals | 82 % | Ability to detect reductions in exposure during periods of risk. |

| Decision consistency | 0,89 | Logical consistency between context and action. |

| Average human/model divergence | 0,17 | Limited average deviation: human behavior well simulated.

|

The performance, achieved without proprietary data, demonstrates the maturity of OSINT as a source of strategic intelligence: public data, when properly processed and interpreted, can rival closed sources.

These practical cases show that OSINT is now an essential source of data for developing strategies, anticipating risks, and understanding them. As a result, OSINT is used in many fields and, in our opinion, can no longer be ignored in any data-related project. In our case, its practical use has even made it one of the pillars of our company’s creation.

Through this case study on open source intelligence, Baptiste and Alexandre demonstrate how the teaching methods used in the joint Mines Paris – PSL and Albert School programs enable students to grasp complex and current issues through practice. By designing a learning tool rooted in real-life situations, they illustrate an approach to teaching that trains individuals to analyze information, assess its reliability, and transform it into a strategic lever. This approach reflects the ambition of Mines Paris-PSL: to prepare informed decision-makers who are capable of evolving in uncertain and highly information-intensive environments.

Training talented individuals capable of linking science and management to the concrete challenges faced by businesses is the ambition of the joint de...