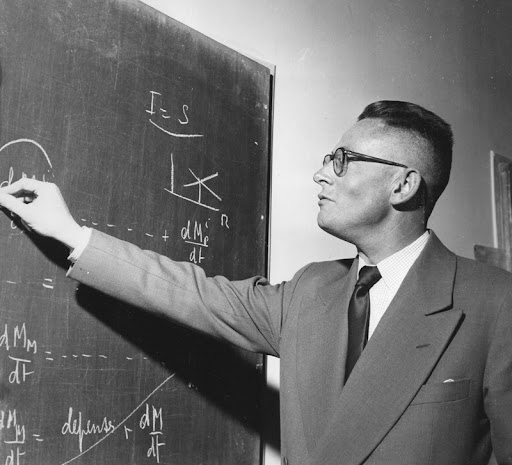

Maurice Allais: a genius of theory and practice to be rediscovered

Rereading Maurice Allais, the brilliant economist who spent his entire career at the École des Mines in Paris, is the best way to remember how scientific excellence flourishes when theory and practice are combined.

As he said in 1954 (in French!) in the prestigious journal Econometrica, “theory is nothing but condensed practice and the opposition between theory and practice is purely artificial. A theory is only valid if it conforms to the facts, and therefore to practice. “The scientific fact is only the raw fact translated into convenient language” [Poincaré, 1927] and “science has no other purpose than to summarize the facts in formulas interpreted by theories” [Bouasse, 1931]. In reality, understanding a phenomenon means being able to establish an abstract model of it. (…) it is a mistake to maintain that science can be done by simply accumulating facts. This path cannot lead anywhere, except to disorder. (…)

In a perpetual back and forth between theory and practice, and by appealing as needed to ordinary logic or its extension that mathematics constitutes, this intelligence, always nuanced and never dismissive of form, but always concerned with logical coherence, strives to discern the essential characteristics of facts, either for the satisfaction of better understanding them on the level of thought, or for the advantage of better utilizing them on the level of action.”

And he concluded a few pages later:

“The science of economics is above all a science of observation and an applied science. The use of mathematics is indispensable as a process of deduction and analysis, but it can only be fruitful if it is based on an excellent knowledge of the facts. This is why it is essential for an economist worthy of the name not to remain narrowly specialized, but to have a broad knowledge, not only of pure and applied economics, but also of sociology, political science and history. ”

Maurice Allais revolutionized the economic analysis of his time in two remarkable works written four years apart and rewarded 41 years later by the Nobel Committee. In A la Recherche d’une Discipline économique (1943), a work later renamed Traité d’Économie Pure, he regenerated the methods of proving the existence of a general economic equilibrium by foreshadowing what would become Lyapunov’s second method; but he also developed, over 900 pages, the applications he envisaged for various economic situations. In 1947, he naturally sought to extend these results to a dynamic (or inter-temporal) macroeconomic universe. In Économie et Intérêt, he renewed macroeconomics – until then based on the “representative agent” – by creating the model of “intergenerational” economies, which would become a standard tool for evaluating pension systems in particular. He emphasized the intergenerational distribution of resources and the political role of the state in this regard, highlighting the shortcomings of the market.

In reality, this great economist was also a great thinker. In several writings from the 1940s and 1950s, he strove to find a “competitive planning” that would make it possible to take into account socialist-type criticisms of the liberal economy and the excessive limitation of freedoms in state economic organizations, which were otherwise ineffective. Maurice Allais demanded that the scientific spirit be free of rigid ideological references and seek only to improve the lot of the greatest number, without ever forgetting the most modest, from whom he himself came. In 1977, he published a work on “L’Impôt sur le Capital et la Réforme monétaire” (Tax on Capital and Monetary Reform) which confirmed this social and scientific orientation.

The great American economist Paul Samuelson wrote in 1982: “If Allais’s early writings had been in English, an entire generation of economists would have followed a different course”. It is difficult to imagine a more exceptional tribute. It is precisely the most important of his “first writings”, Économie et Intérêt, whose first English translation is being celebrated on Thursday, February 13, 75 years after its first edition, produced by the Imprimerie Nationale. With such a publisher, there was a good chance that the work would remain confidential. It remained so, and not only abroad, but unfortunately also in France. However, this 800-page book contains a wealth of discoveries, many of which have since appeared in the writings of other researchers – often American – who have now recognized and made public the precedence of Maurice Allais. This is the case of the overlapping generations model, which was developed by Paul Samuelson (1958) and then Peter Diamond (1965), and also of the refutation of the Ricardian hypothesis that public debt never affects economic efficiency. The same applies to the inadequacy of the market to ensure a satisfactory intergenerational distribution of income, which must result from a political decision. These are all aspects that many economic leaders have downplayed, thus causing many of the current difficulties.

These topics will be the subject of the debate organized at the School on Thursday, February 13, starting at 5:15 pm, at the Espace Maurice Allais and by videoconference.

Faced with the acceleration of climate disruption and its already visible impacts – deadly heat waves, floods, giant fires, the weakening of agricultu...