Interview with Franck Guarnieri: blue engineering at the heart of teaching with Mines Paris pour l’Océan

Since 2022, Mines Paris – PSL has been offering an educational program dedicated to ocean preservation, aimed at enriching understanding of the challenges of blue engineering, the technological component of the blue economy. This program enables future engineers to confront major contemporary challenges. Over the three years of their Civil Engineering Cycle, students spend several weeks immersed in specific themes.

Interview with Franck Guarnieri, Research Director at the Centre de Recherche sur les Risques et les Crises (CRC) of Mines de Paris – PSL in Sophia Antipolis.

France has the second-largest exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the world, but we hardly have the means to know it in detail and protect it. We lack boats, engineers and researchers. The ocean plays a vital role in climate regulation, human nutrition and the essential balance of life in all its forms.

The Centre de Recherche sur les Risques et les Crises has been conducting research on the marine environment since the early 2000s. We worked on risk prevention for offshore industrial installations, mainly oil and gas platforms, for Total Energies R&D. We have also collaborated with EDF R&D to prevent the risk of ships colliding with offshore wind turbines. Three PhD students are currently working on a thesis on the safety and security of the marine environment.

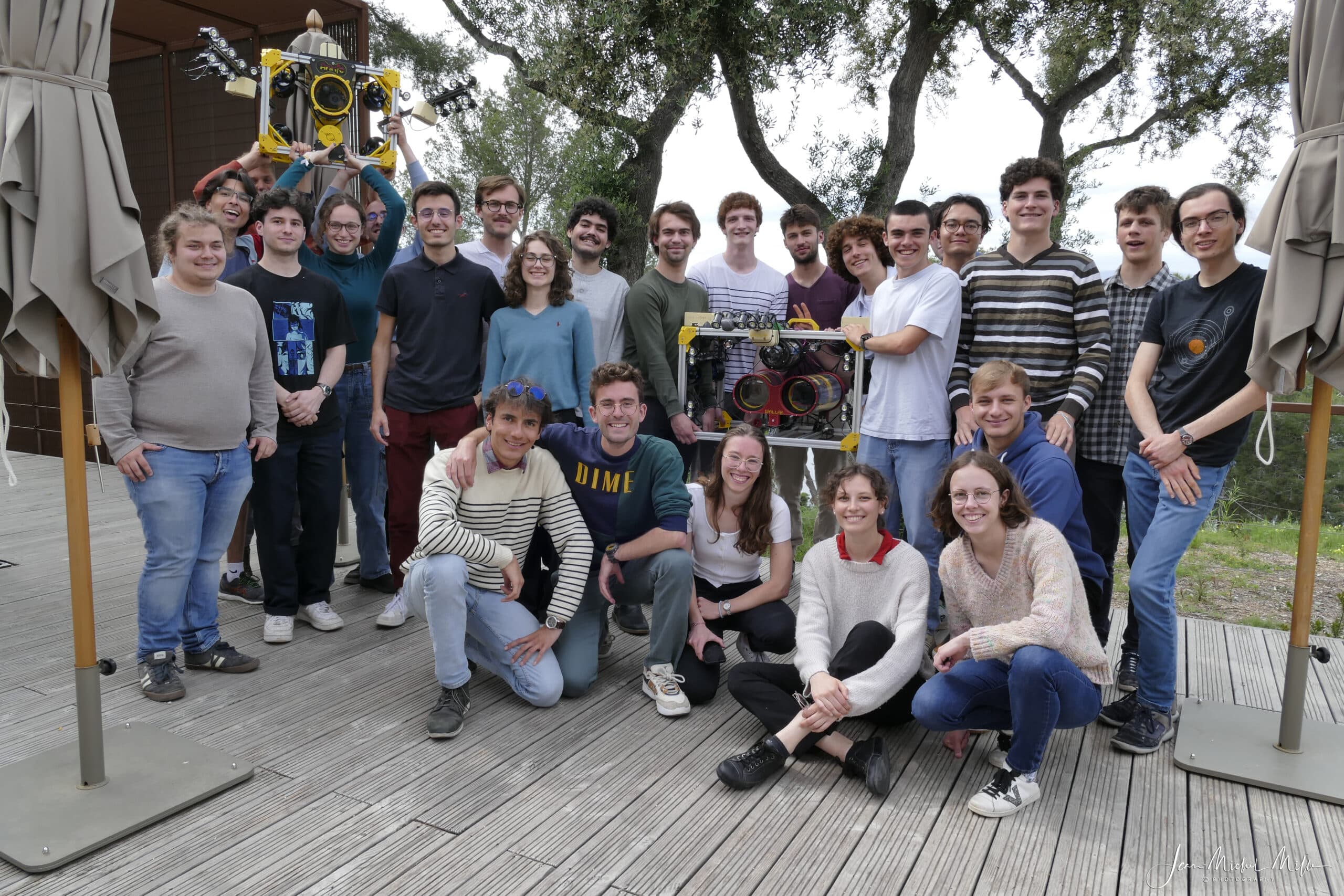

The growing number of students in the Civil Engineering cycle has led the school’s management to launch a call for new courses. With Sébastien Travadel, we created the MIG “Océan” (Métiers de l’Ingénieur Généraliste), a three-week course in the first year, and then developed an engineering project entitled “Underwater: underwater robotics”, a ten-week course in the second year. In fact, we have established an educational continuity in blue engineering, directly linked to the Côte d’Azur and the Mediterranean Sea. This has given rise to the Mines Paris pour l’Océan educational and research initiative. It aims to actively involve us in the region, from Monaco to Perpignan, by collaborating with marine science players such as the Oceanographic Institute of Monaco, the University of Nice, IFREMER in Toulon…

Annie, photographed on the wreck of the Robust II, off Golfe Juan (06). This is one of two ROVs (remotely operated underwater vehicles) in the Underwater 2024 engineering project.

First photos of Annie, at Cap d’Antibes on April 30, 2024.

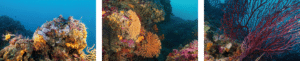

The Mediterranean Sea is considered the most polluted sea in the world. As a semi-enclosed sea, pollutants accumulate rapidly. Surrounded by many densely populated and industrialized countries, it receives untreated sewage, industrial and agricultural waste. Intensive tourism along the coasts generates large quantities of waste, and inadequate waste management contributes to the accumulation of plastics in the sea. The Mediterranean is also a busy shipping lane, resulting in fuel discharges and oil spills. Add to this gloomy picture excessive, even destructive, fishing, and you have all the reasons to mobilize students! The region is particularly sensitive to this cause.

In 2025, Nice will host the United Nations meetings on the Ocean. In 2023, Antibes has inaugurated a fantastic space to raise awareness and educate the general public about the underwater coastal biodiversity of the Cap d’Antibes. Preserving marine biodiversity is also a priority for the Département and the Région. The region’s scientific community is particularly dynamic, companies in the Var and Bouches-du-Rhône are global heavyweights, and Sophia Antipolis-based startups are promising.

Yes, we did! There was a real fit with the area, and we had local and regional institutional and scientific partners who were very keen to collaborate with a leading engineering school like ours.

As for the students, they are enthusiastic about the initiative. When we show them IFREMER’s underwater robots, capable of descending to 6,000 meters, there’s an immediate “wow” effect, thanks to our world-renowned technological excellence. And if the aircraft carrier

Charles de Gaulle is present in Toulon’s harbor, it obviously stimulates the imagination! So we responded intelligently to the call from the school’s director of studies. The gamble paid off. The “Ocean” MIG is very popular, and every year we have more applicants than places available. The “Underwater” engineering project is growing in numbers every year, with almost 40 students expected by 2025.

The first two classes of the “Ocean” MIG worked on the contribution of satellite imagery, one on the detection of macro-plastics in the Mediterranean (2022/2023), the other on coral reef bleaching in French Polynesia (2023/2024).

The Underwater 2023 project, conducted in partnership with the French Office for Biodiversity and the Cap Corse et Agriate Marine Park, resulted in the design of two underwater robots, Léon and Eugène, capable of taking images to study a coralligenous: rhodolite.

Underwater 2024, in collaboration with the Saint-Raphaël archaeological museum, focused on underwater archaeology. The aim was to map a shipwreck off Cap d’Antibes to measure its state of conservation and its colonization by flora and fauna. Two underwater robots, Wall-Y and Annie, remotely operated from the surface, were also developed.

As part of Underwater 2024, second-year Civil Engineering students have designed two machines, Annie and Wall-Y, capable of descending to a depth of 300 meters and bringing back 2D and 3D images.

Every year, we propose very ambitious projects to our students, challenges that force them to surpass themselves. With the deep sea, they have to confront a complex environment and often difficult conditions for deploying their technical solutions at sea. They are also accountable to a partner who is fully involved in the educational project.

We’re developing a low-cost, high-quality data collection solution in the 0-300 m depth zone. Why do you want to do this? Today, the ocean industry sends robots to depths of 10,000 meters, and the economics of deep-sea robotics have been around for a long time, proving to be extremely efficient. The scientific players in this field, such as IFREMER, have machines to work at depths of between 2,500 and 6,000 meters. We found that there were no robots fully adapted to the coastal zone between 0 and 300 meters, as this is not an economically exploitable zone, except for fishing. Yet this zone is a crucial sentinel of the state of living organisms.

Today, designing a robot for these depths is neither complicated nor expensive. However, the real challenge lies in the onboard payload (listening, vision, sampling). This is an area of technology in which there is still too little investment, as marine area managers are sorely lacking in funding. The rare measurement campaigns are extremely costly. As there is no established market, there is plenty of room for creativity, which will eventually lead to high value-added solutions.

Students choose our courses because of our reputation, our high standards and our resources. We have a fully equipped workshop covering almost 100 square meters, including CAD/CAM software, fluid mechanics software, a fleet of 3D printers, machine tools, electronic benches and calculation servers.

Equally encouraging is their awareness of the many threats facing our planet. Seas and oceans are on the front line, but their vulnerabilities are often overlooked. So it’s very positive that they’re joining us in such numbers.

As the courses take place in Sophia Antipolis, students are immediately connected to the area and develop a special relationship with the marine environment. For example, on the second day of Underwater, they embark on a mission designed to raise their awareness of the complexities of underwater data collection. The least reluctant or bravest, in the middle of February, in 13-degree water, don wetsuits and take their first underwater shots. This is their first taste of the realities of the underwater world. During the 10-week course, sea outings are frequent, usually on Thursday afternoons, instead of sports.

Underwater 2024 students’ first outing to the sea.

Last but not least, the commitment we make to a third party in the expectation of an operational result boosts their motivation tenfold.

Students use CAD software to design the structures of the craft. They choose pressure-resistant materials and master assembly and sealing techniques.

In electronics, they design circuits for robot control and calibrate sensors for navigation and data acquisition.

In programming, they create software for remote operation and image processing, master underwater image capture techniques and develop analysis software.

In hydrodynamics, they optimize propulsion systems. They gain experience in prototyping, assemble robot components, carry out tank and sea tests, and solve technical problems.

In project management, they plan, coordinate phases and work as part of a team. Teamwork and communication skills are reinforced, promoting effective collaboration and clear presentation of results.

Finally, they acquire skills in safe subsea operations, implementing safety measures and developing environmental awareness, applying best practices to minimize ecological impact.

The subject of the MIG Ocean, which starts in November, will be announced in September. It’s a secret. Every year, we want to surprise our students, to arouse their interest and desire, especially as the number of places is limited to sixteen. IFREMER Toulon will be at our side, a wonderful recognition of our efforts and a strong vote of confidence in the students’ future work.

For the Underwater 2025 engineering project, we’ve set no limit to the number of students we can welcome. Spending ten weeks in the South and being cut off from the rest of the class can put some people off. The absence of limits encourages people to come as a group. It’s like moving a corridor from the Meuh to Sophia Antipolis! Mission 2025 is currently being defined. Here again, we don’t communicate much, except to say that we’re aiming for depths of 300 meters or more.

A “blue engineering” option could of course find its place in the third year. However, given that part of the course has to take place in Paris and that the timetable is fragmented, we need to take the time to think about it.

France has the second-largest exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in the world, but we don’t have the means to know it in detail and protect it. We lack boats, engineers and researchers. Today, in France’s top engineering schools, there is talent that could change the game! And not just in industrial and economic terms. The ocean plays a vital role in climate regulation, human nutrition and the essential balance of life in all its forms.

We reach several dozen students a year, who are enthusiastic about the subject. We hope that some of them will choose this career path thanks to these courses. In three years’ time, I’m convinced that some of our students will have their first job in blue engineering.

A research director, Franck heads the Centre de Recherche sur les Risques et les Crises (CRC) at Mines de Paris – PSL in Sophia Antipolis. A keen scuba diver and committed to preserving the seabed, he has co-written the book Petite philosophie de l’ingénieur (PUF, 2021) with Sébastien Travadel, a professor at the École des Mines de Paris and a keen sailor. This book sheds new light on engineers’ relationship to their profession, to science and to ethics, enabling engineering to become part of an ecological way of thinking supported by a system of values in line with current planetary issues.