How much must employers pay to attract executives outside urban areas?

The question of regional economic development is, first and foremost, a chicken-and-egg story. Just as the chicken comes from an egg laid by another chicken, a territory needs workers to thrive—but those same workers will only settle there if the territory is attractive enough. A dense area offers better career prospects but also provides sought-after amenities such as schools, hospitals, theaters, transport, and public services—so many reasons why workers tend to prefer more developed regions.

We examined this dynamic through a specific question: how do companies located in sparsely populated areas nevertheless manage to attract talent? One possible answer can be found in the economic theory of compensating differentials, which explains wage disparities based on both professions and territorial heterogeneity.

According to the theory of compensating differentials, wage differences arise from both individual skills and working conditions—including quality of life. The more challenging the conditions, the higher the wage must be to attract workers. In other words, if two individuals have equivalent skills, and one lives in a less dense area offering fewer amenities, that individual should logically be paid more (to compensate for this disadvantage).

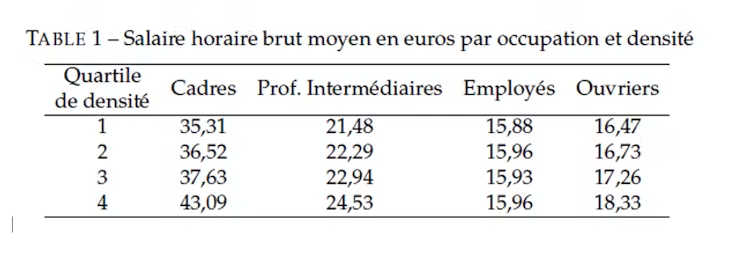

Yet, data tell a very different story. As shown in Table 1 below, average gross hourly wages actually decrease with density. For executives, for instance, they fall from €43 in the most densely populated areas to €35 in the least dense ones—a difference of more than 23%.

Source: authors. Author provided – no reuse

Two key insights emerge from these figures:

In short, it is not the absolute wage that compensates for low density, but rather the relative standard of living, which can be measured by the ratio between income and real-estate prices.

How can we verify that living in a less dense area actually results in a higher standard of living—especially for highly qualified workers? To answer this, one must compare not just wages, but the ratio between income and cost of living, estimated here by including real-estate prices.

This is a complex exercise, as many factors come into play: individual skills (age, education, gender), labor market characteristics (job supply and demand, corporate organization, exports, automation), and territorial elements (density, infrastructure, agglomeration effects). If these variables are not systematically accounted for, one risks confusing the true effect of density with other determinants.

To overcome this challenge, we mobilized an extensive dataset: all employment contracts signed in the manufacturing sector in 2019, enriched with firm-level and local indicators. This wealth of statistical information enabled us to isolate as precisely as possible the specific effect of density, by comparing similar profiles across territories of varying density levels.

The results are clear. As density increases, nominal gross wages rise—but real-estate purchasing power declines. A 1% increase in density raises by 0.15% the number of working hours required to buy one square meter of housing. In other words, wages increase with density, but not enough to offset the surge in real-estate prices.

This effect is particularly significant for executives. They experience the strongest wage increases in dense areas—but also the greatest losses in real-estate purchasing power. By choosing to settle in a less dense area, they accept a lower salary but benefit from a substantial gain in housing affordability.

Why is this “premium” more pronounced for executives? From the perspective of compensating differentials, our results suggest that executives are the most sensitive to the benefits associated with density, since they are willing to give up relatively more purchasing power to enjoy those benefits.

Our findings should, however, be interpreted with caution. Several aspects warrant further investigation:

Education level: due to the lack of data on educational attainment, part of the observed differences may reflect disparities in workforce profiles between dense and less dense areas. Better isolating this variable would likely accentuate the identified premium.

Family dimension: mobility decisions are rarely made individually. A territory’s attractiveness also depends on employment opportunities for spouses, schools for children, and healthcare facilities.

Life-cycle effects: priorities change over time. The proximity of a high school matters little without teenage children, while access to healthcare becomes crucial with age.

Impact of COVID-19 and remote work: our data predate the pandemic (2019). The health crisis has reshaped the trade-off between major urban centers and less dense areas, giving new impetus to remote work.

That being said, low-density areas are natural candidates for reindustrialization—if only for obvious land availability reasons. Attracting skilled workers there is a major challenge for firms. Public policy must take into account how employment attractiveness varies with density, while companies can find a balance by relocating to these areas and benefiting from lower living costs—provided that infrastructure and amenities are not deterrents.

The widening gap between (very) dense and less dense zones risks depriving many territories—with significant industrial redevelopment potential—of a sustainable revival. To solve this chicken-and-egg problem and initiate virtuous circles, only coordinated action between public authorities and companies at the local level will enable lasting reindustrialization—benefiting employees, businesses, and territories alike.