Cracked houses: how to cope with the effects of climate change?

Increasingly widespread, the phenomenon of cracked houses can be explained by a mechanism that occurs during periods of drought: clay shrinkage and swelling (CSW). When clay soils dehydrate, they contract, sometimes causing major damage to buildings.

The two key factors in the appearance of these cracks are the presence of clay soil and the recurrence of drought episodes. While the nature of soils is based on immutable geological characteristics, droughts are becoming more and more frequent due to climate disruption caused by human activity.

These episodes of drought can be considered as negative externalities: collateral effects of economic activities that are not taken into account by those responsible.

What is the impact of this phenomenon? And what lessons can we learn from the phenomenon of cracked houses to better collectively manage the future consequences of climate disruption?

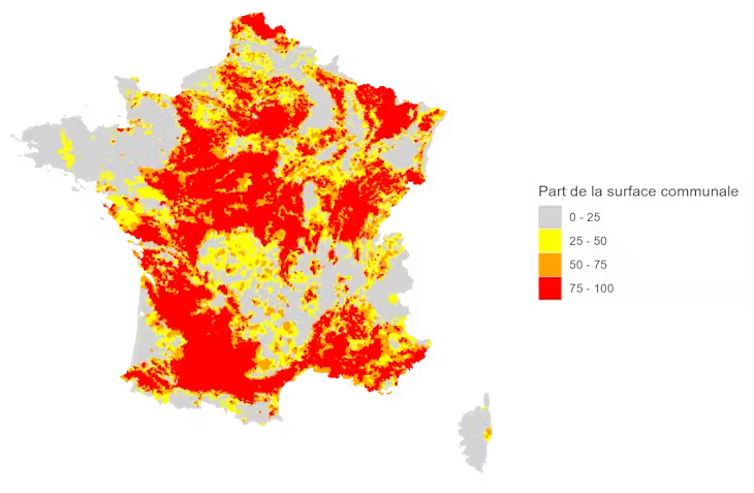

The Bureau de recherches géologiques et minières (BRGM) estimates that 48.5% of the French territory is moderately or severely exposed to RGA. The phenomenon of cracked houses is therefore of national importance.

Percentage of communal surface exposed to medium or high RGA risk. BRGM

Percentage of communal surface exposed to medium or high RGA risk. BRGM

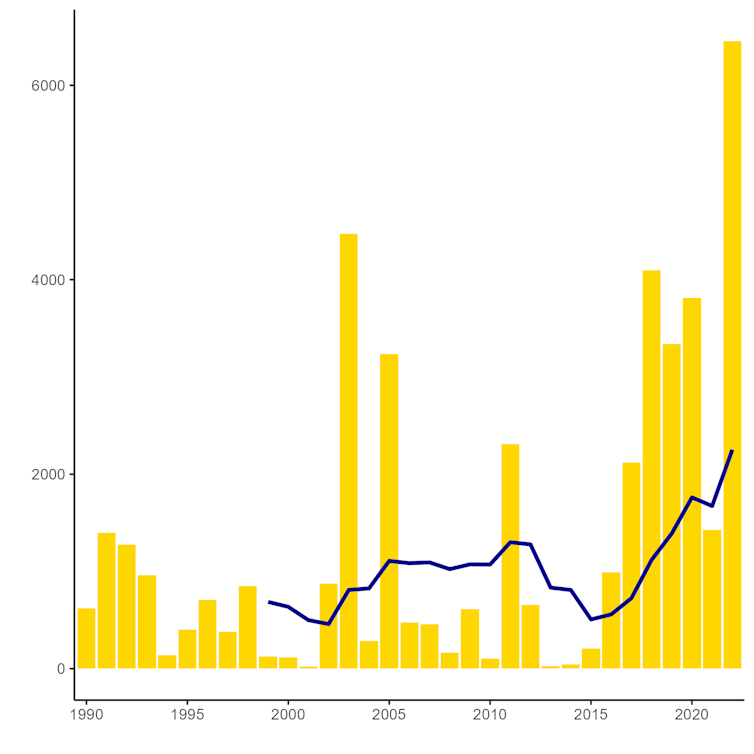

It is also growing rapidly. The following figure shows the trend in the number of natural disasters due to drought and landslides caused by drought and soil rehydration, two categories of disaster that can be compared with the RGA.

Number of drought-related natural disasters in France between 1990 and 2022. Assisted management of risk-related administrative procedures (GASPAR)

On the one hand, we can see that droughts follow a certain periodicity at intervals of around ten years, with a first cycle ending in the early 2000s, a second ending around 2014 and a third that has not yet come to an end. On the other hand, the number of occurrences increases sharply in the latest cycle observed, as illustrated by the 10-year rolling average shown in blue. As drought is the main cause of RGA, such an increase in drought episodes can only aggravate the phenomenon of cracked houses.

However, this phenomenon is very unevenly distributed across the territory, since it depends on soil constitution. This heterogeneity is also coupled with heterogeneity in terms of heritage. According to a 2021 estimate by the Service des données et études statistiques (SDES), 10,430,299 homes would be exposed to a medium to high risk of RGA. However, there are major differences according to property type. Almost 45% of exposed homes were built after 1975, and are more vulnerable than older buildings.

Heterogeneous exposure to the hazard makes it difficult to draw up and implement a national policy, which, by definition, is intended to apply to everyone and to the whole territory.

Nevertheless, this difficulty seems to be common to many of the consequences of climate upheaval (rising urban temperatures and pollution, rising water levels, difficulties for localized agricultural crops such as vines, etc.). The RGA’s public-policy approach can serve as a model for the problems that lie ahead.

The appearance of cracks generates significant repair and rehousing costs. To date, the preferred solution has been financial compensation through private insurance or public funds. However, these solutions do not appear to be sufficient, let alone adequate to deal with the future consequences of climate change.

All recent reports from major public institutions express concern about the inability of the “CatNat” natural disaster compensation system to cope with the consequences of climate change. This system enables individuals, businesses and local authorities to receive compensation in the event of a natural disaster. In particular, Christine Lavarde points out in her information report to the French Senate that “it is estimated that the cumulative cost of drought claims between 2020 and 2050 would represent a cost of 43 billion euros, i.e. a threefold increase compared to the previous three decades. As a result, the CatNat scheme would no longer be able to generate sufficient reserves to cover claims by 2040.

Other solutions must therefore be considered, for example:

What’s more, solutions that simply compensate for damage do not take into account the reduction in property value. The probability of RGA, even if the house is not cracked, is integrated by potential buyers and has a direct impact on the market price. According to our estimates, a 1% increase in exposed surface area in the commune leads, on average, to a significant reduction in price per square metre of 29 euros. Taking this shortfall into account would further increase the amounts payable…

In 2022, France emitted 404 million tonnes of CO₂ equivalent, 25% less than in 1990, the reference year for the Kyoto Protocol. Although headed in the...