How skiers are adapting to the lack of snow

Little snow this winter, with half the slopes closed at Christmas and sometimes poor snow conditions for the February holidays. The ski industry is one tourist activity that has been hard hit by global warming. How are skiers responding to this situation? Are they heading for the high-altitude Alpine resorts or the sunny Canary Islands?

How are they adapting to a future that is increasingly less white?

“Ski 365 days a year”. This advertising slogan from the 1980s for Tignes, an alpine resort built from scratch, bears witness to a bygone era: the development of winter sports and the belief in eternal snow. Glaciers were melting and the snow cover was shrinking. Ski lifts for summer skiing in France now only operate for a few weeks a year. The ski areas are also opening later for winter skiing.

Last year, the famous Savoie resort in the Vanoise massif closed its lifts on 1 July after only 10 days of operation, and postponed the opening of its high-altitude ski area until after All Saints’ Day. This municipality now has 30,000 beds – the scale that has replaced counting the number of inhabitants in resorts – and nearly 500 snow guns – the name that has replaced the less graceful “snow cannon”.

Over the last 50 years, the duration of snow cover in the Alps has fallen by around a month, and average snow heights have dropped by several centimetres per decade.

This sentence sums up the results of a major international study. The study looked at data collected between 1971 and 2019 at more than 2,000 weather stations in the European Alps. It uses numerous definitions and a whole series of hypotheses and models which, as with any scientific work, have their limits and are open to discussion.

For example, the presence of just one centimetre of snow is enough to define a snowy day, a threshold that obviously won’t satisfy skiers. Furthermore, the estimated trends are often not statistically significant, because the inter-annual variability of snow conditions in the mountains is extremely high, even though the observation period, a few decades, is not that long.

The historical decline in snowfall is also well established by national studies, whether for the French, Swiss or Austrian Alps. Note that the reduction in snow depth and duration is more or less marked depending on the local situation, in particular altitude, latitude, and the exposure and slope of the slopes.

This makes it difficult for skiers to compare the reliability of snow cover between resorts when choosing their ski area. The average altitude of the ski area is only a very rough approximation, and knowing the precise interval between the low and high points of the resort does not provide any more relevant information for making a decision.

There’s nothing surprising about the trend outlined in previous studies: as soon as the mountains warm up, slightly more so than the plains, it follows that it rains more than it flakes, that the snow falls in smaller quantities, melts more quickly, arrives later at the start of the season and leaves earlier at the end. Goodbye to the snowflakes of yesteryear.

When it comes to adapting the ski industry to the decline in snow cover, supply and demand, i.e. resorts and skiers, are on an unequal footing. On the one hand, there are specialised facilities and people, rooted in the area and not very mobile; on the other, there are tourists and holidaymakers, i.e. labile consumers who move quickly and easily.

On paper, snow consumers are faced with three options: skiing elsewhere, skiing at other times of year, or choosing other leisure activities.

The first, unlike the other two, does not necessarily lead to a drop in the number of skier-days in the mountains (i.e. users paying for ski lifts per day). On the other hand, it does redistribute the cards in favour of resorts with more reliable snow cover. In other words, the high-altitude resorts. Tignes and Val Thorens rather than Abriès or Chamrousse, not to mention the resorts in the Jura, Pyrenees, Vosges and Massif Central.

It’s a real disappointment to find chairlifts and gondolas empty after planning your skiing holiday in advance. Adapting your skiing schedule to that of a more reliable snow supply – for example, going on a snow holiday in February rather than at Christmas or Easter – reduces the length of time you can spend in the resorts and, as you may have noticed with a touch of annoyance or more, lengthens the queues at the bottom of the ski lifts and at the entrances to the self-service lounges and mountain restaurants. Not to mention the saturation of the car parks…

All this congestion can end up dampening skiers’ spirits and discouraging many of them. With no guarantee of snow and congestion, winter tourist destinations that guarantee sun, warmth and fine sand are becoming less attractive. Especially as exotic beaches are less crowded than in summer.

Few studies attempt to pinpoint the behaviour of skiers. This is paradoxical, given that demand for winter sports is falling in Western countries, which should encourage a better understanding of the reasons behind it.

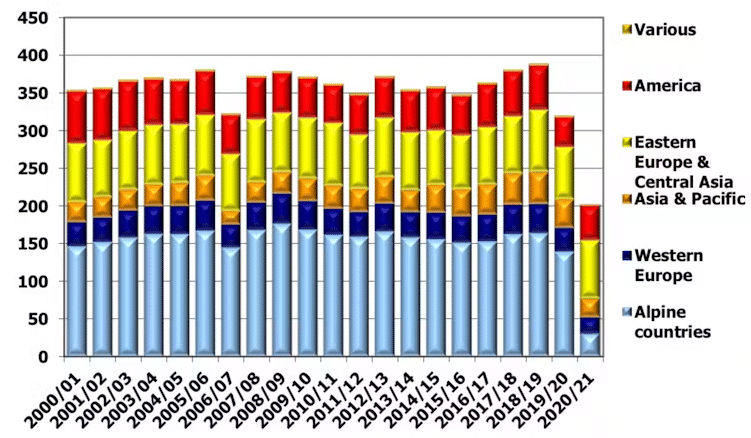

Skiing is a mature market. Measured in terms of the number of skier-days, global demand has fluctuated around 350-380 million per year since the turn of the century. It has been falling slightly since 2009-2010 in the Alps, which account for around 40% of skier-days on all the world’s slopes.

This downward trend would be reinforced if we included the winter of the pandemic. Remember the images of ghost resorts due to the closure of ski lifts and the drastic limits imposed on travel at the time? With the very French administrative precision that in the mountains the walking radius around the home corresponded to 100 metres of difference in altitude and not, as elsewhere in France, to the distance that could be covered.

However, don’t blame the lack of snow for the decline in demand for winter sports, which means that skiers have adapted perfectly to global warming. Demographics may still be the primary cause, but other factors are also at play. The ageing of the population is reducing the number of downhill skiers, and this is not being offset by the arrival of sufficient numbers of new skiers.

It’s true that it’s not an instantaneous pastime – it takes time to master your pace and make the right turns. Nor is it necessarily a pleasant pastime: nails, sore feet, foggy glasses, falls, collisions and so on. For some, once the chore of taking off their shoes with hooks is over, the return to the flat is experienced as the best moment of the day. Especially over a hot chocolate and blueberry tart!

What’s more, in France, Switzerland and Austria, there are fewer and fewer snow classes for schoolchildren in the big cities. Finally, skiing is still a very expensive pastime. It is reserved for a small part of the population. By successive shrinkage: those who go on holiday, even fewer who go on winter holiday, and even fewer who choose to go to the mountains.

[Nearly 80,000 readers trust The Conversation newsletter to help them better understand the world’s major issues. Subscribe today]

The clientele of ski resorts has a well-known profile: fairly high income, above-average level of education, usually living in the centre of large cities; characteristics that overlap but with a clear geographical difference: the CSP+ in Brest spend less time on winter sports than those in Grenoble.

According to the very few and too old studies available, when asked how they were adapting to the decline in snowfall, skiers would prefer to go up to higher altitude resorts and shift the dates of their stay to the most favourable weeks rather than change their destination to the sun or elsewhere.

You’ll notice that I haven’t said anything about customers switching to activities other than skiing. That’s because this change depends more on the resorts’ adaptation to global warming and their proposals for snow-free mountain leisure activities, a thorny subject but one that has been well identified by researchers, elected representatives and even auditors from the Cour des Comptes.

Until now, resorts have mainly adapted by sliding down the technological slope, that of grooming and artificial snow production, also known as ‘cultured’ snow in France, ‘programmed’ snow in Italy, or ‘technical’ snow in Germany.

Many resorts are planning to pursue this line of defence against climate change by increasing the number of snow cannons and back-end facilities (pumping rooms, reservoirs, etc.). It’s a course of action that is not without harmful consequences for the environment, but also for skiers, even those least concerned about the future of the planet.

For the latter, the most obvious inconvenience is the increase in the price of ski passes and therefore the higher cost of ski leisure. Artificial snow requires heavy infrastructure and high expenditure to make it work; investments and technical costs that are added to those of the ski lifts.

And ski passes are already expensive. You can expect to pay 63 euros per person per day for access to Espace Killy (Tignes-Val d’Isère), 57 euros for Portes du Soleil (Avoriaz-Champéry) and between 20 and 40 euros for smaller ski areas. The high average income of skiers does not mean that the resorts are immune to the erosion of their customer base in the face of rising prices. They are also faced with a decline in quality: gliding along a white ribbon of piste, cluttered and bordered by yellowish, earthy grass, is singularly lacking in charm.

It’s still better than skiing under a bell, you might say. Ski domes have many customers and new ones are even being built. True, but their slopes are usually just a few dozen metres long and they are mainly being built in China, where skiing is not traditionally associated with natural snow.

In Japan, on the other hand, indoor ski centres are closing one after the other. They are experiencing the same decline in customer numbers as outdoor skiing, which is particularly marked and rapid in this country with so many centenarians.

Skiing under a bell is also an amusement park, and as such is also facing competition from amusement parks of all kinds. This rivalry is all the more disadvantageous for the ski domes because customers don’t have to get equipped and get active, but simply passively follow the attractions in their everyday clothes and boots.

In order to ski 365 days a year in an ultra-artificial, globish version, the municipality of Tignes at one time envisaged building a “Ski-Line of in-door pistes”. 400 metres of covered sliding all year round in a giant fridge, with a chairlift for skiers and, next door, an artificial wave pool for freshwater surfers.

Ce projet démesuré est resté à ce jour dans les cartons. Il ne devrait pas en sortir. La fin d’un monde est passée par là : celui d’une société sans pandémie, d’un accès immuable à une énergie et une eau bon marché ; mais aussi d’une clientèle indéfectible de skieurs consommateurs, au porte-monnaie sans fond ; et peut-être désormais plus préoccupés par leur empreinte sur la planète – souhaitons-le.

François Lévêque is the author of “Les entreprises hyperpuissantes. Géants et Titans, la fin du modèle global? His book was awarded the Prix Lycéen du Livre d’Economie in 2021.

François Lévêque, Professor of Economics, Mines Paris

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.