How are organisational and managerial innovations deployed?

Since the 2010s, companies have been taking an active interest in new management and organisation methods (NMMO): agile methods, “liberated enterprise”, “holacracy”, “opal” organisation… these are all concepts in vogue at a time when companies are being urged to become responsive, adaptable and innovative, as we point out in our recent book, Les nouveaux modes de management et d’organisation, innovation ou effet de mode? (La Fabrique de l’Industrie).

Referring to these models (and preferably to several of them) is useful, because they provide a framework for thinking and acting. However, they rarely come with instructions for use, and their effects will depend considerably on how they are deployed in organisations.

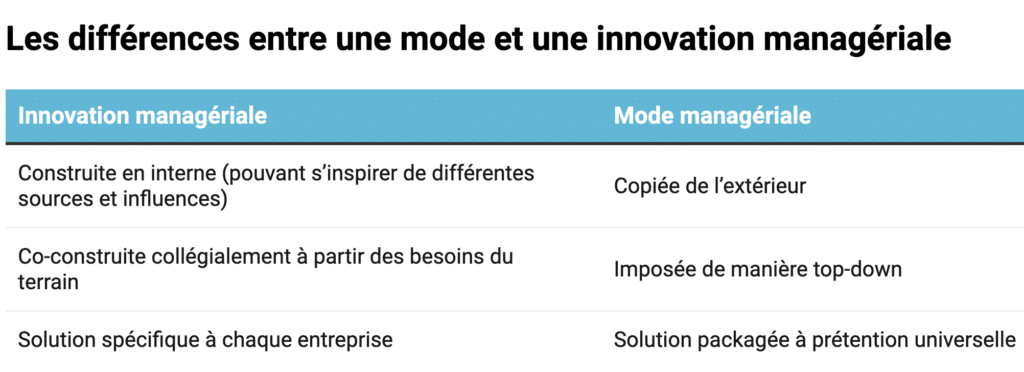

Broadly speaking, there are two main ways in which they can be deployed. In the first case, the new organisational model is built by the internal players, who may well draw inspiration from existing models, but make the effort to adapt them to meet their own needs and specific characteristics (environment, business sector, organisational and managerial culture, interplay of players, etc.): these methods then hybridise with other internal practices and give rise to original uses, the fruit of a genuine process of organisational innovation.

In the second case, the company is content to follow a model in the manner of a recipe to be applied, without taking account of the specific characteristics of the organisation, and then falls into the trap of a fad.

In our recent work, we have identified four possible deployment processes. We drew on a corpus of 17 organisations experimenting with the new modes in more or less radical ways, ranging from self-managed associations to divisions of large groups, in a variety of sectors.

The first configuration involves inventing the model from scratch. This is often found in self-managed organisations that are keen to invent their own alternative model. They often suffer from a lack of references to guide them through the twists and turns of their experiments. Despite the long history of this movement, it remains little studied by the management sciences. Self-management, the practical application of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s nineteenth-century anarchist political philosophy, has been experimented with throughout the twentieth century (Paris Commune, Russian soviets, German workers’ councils, Hungarian revolution, etc.).

The advantage of this approach is that it ensures the deployment of practices that are completely original and adapted to the aspirations of their members, who are often quite ideologically marked. However, a study of four self-managed organisations, cooperatives and associations, reveals that they often encounter the same difficulties, which ultimately leads them to adopt fairly similar organisational practices. As a result, they run the risk of “reinventing the wheel” each time, in a time-consuming and energy-intensive process that requires many years of trial and error and can end up exhausting members.

At the other end of the spectrum, managers may be content to copy and paste a “turnkey” model onto the existing organisation, even if it’s in a brutal way. They may be seduced by a book they have read, a conference given by its author, or the example of a company that is the subject of media buzz (such as the French companies Favi, Poult or Chronoflex, emblematic of the ‘liberated’ business movement, which seeks to empower their employees within less hierarchical organisational structures).

One of the organisations on our panel followed this path: inspired by their reading, the young buyers were seduced by the solution proposed by a consultancy specialising in “holacracy”, which promised them a transformation of decision-making methods and the distribution of responsibilities within the company in six months. The very short duration of this transformation, coupled with the lack of preparation on the part of the employees, who struggled to get to grips with the sometimes abstruse vocabulary of holacracy, led to organisational confusion which resulted in problems with productivity, quality and the social climate.

This brutal transformation, carried out without any real co-construction, even led to the paradoxical return of the manager as a figure of command and responsibility, prompting managers to adapt holacratic principles in order to truly venture into an innovative approach.

Many companies also mix methods and tools borrowed from fashionable models, producing not a coherent hybrid adapted to the company, but a monstrous chimera. This is particularly the case when organisations seek to draw inspiration from different models without working on how they fit together, the third configuration we have observed. The “inconsistencies in the system and an accumulation of tools with no real shared philosophy” can lead to a “loss of meaning”, to use the words of consultant Élodie Montreuil in an article published in 2016.

This phenomenon has been particularly visible in Western adoptions of the Japanese model (Toyota Production System, now Lean management), which have often retained only a few tools (5 zeros, 5S, Muda, etc.), forgetting the overall philosophy that guided them.

This is also the case with certain conceptual “cobblings” of large groups which amalgamate almost all the NMMOs, while embedding them in a hierarchical pyramid system. Some of the employees we interviewed referred to them as “hierarchy + circles”, “home-style holacracy” or “agile governance”, but few seemed to know what they were all about.

Finally, the last configuration we observed was the collective appropriation of different models. This was the case with an “impact” association that had noticed that it was drifting towards a hierarchical organisational model, whereas it was aspiring to develop “shared governance” that was more in line with its social mission.

To do this, it drew inspiration from various models (holacracy, agile methods, opal principles) without trying to copy them all to the letter: it drew on the elements that would enable it to structure its transformation, while experimenting with those that seemed most relevant to its organisational philosophy and operational imperatives, thus giving rise to new practices.

This work of appropriation was carried out collegially by means of meetings in small groups (on a rotating and voluntary basis) to define the major organisational principles, then to put them into operation. This long-term process ensured that the new organisation was adapted to everyone’s aspirations and realities. This process of adaptive experimentation continues to this day, as certain shortcomings and limitations become apparent.

Beyond the organisational models chosen, the way in which they are deployed is just as important, as it profoundly reflects the way in which organisational innovation is approached. Ultimately, the ongoing appropriation and adaptation of the models and the role given to the players on the ground in this process are the cornerstone of any managerial innovation. Failing this, there is a great risk of falling into the trap of fads, which ultimately empties the innovation process of all substance.

![]()

Suzy Canivenc, Associate Researcher at the Chair for the Future of Industry and Work, Mines Paris

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.