Reliable, sober, and explainable AI: studying its mathematical foundations at the CMA

The research conducted at CMA is based on a strong conviction: AI cannot be limited to the accumulation of data and parameters. To be reliable, interpretable, and truly useful, it must be based on explicit mathematical models.

This is the spirit behind one of the PR[AI]RIE-PSAI (PaRis Artificial Intelligence Research InstitutE – Paris School of IA) chairs held by Jesus G. Angulo at the CMA. Created in 2019 by our PSL University, the CNRS, Inria, the Institut Pasteur, Université Paris Cité, and a group of industrial partners, PR[AI]RIE is one of four interdisciplinary AI research institutes set up as part of the national AI strategy announced by the President of the Republic in 2018. PR[AI]RIE-PSAI aims to become a world leader in AI research and higher education, with a real impact on the economy and society.

Within J. G. Angulo’s PR[AI]RIE-PSAI chair, mathematical morphology provides a common language for describing complex shapes, structures, and spatial relationships. It allows concepts such as data geometry, topology, and variability to be formalized where purely statistical approaches reach their limits.

The context and objective of the chair is to combine the power of neural networks (convolutional or transformers) with rigorous mathematical methods of image/data processing. Working on a common non-linear theoretical basis derived from mathematical morphology, certain paradigms are integrated into neural networks:

Another major focus at CMA concerns the hybridization of machine learning and mathematical optimization. This research, led in particular by Sophie Demassey, has applications in many industrial systems, including drinking water networks, energy management, and storage. In these fields, decisions must comply with strict constraints: physical capacities, safety rules, and energy costs. However, while deep learning models are effective at predicting behavior based on historical data, they do not guarantee the feasibility or optimality of the proposed decisions.

The solution developed at the CMA consists of combining prediction and optimization. In the case of energy management for water networks, a neural network learns to predict plausible storage profiles based on past data. These predictions are then used as the starting point for a combinatorial optimization algorithm, which is responsible for correcting and certifying the right solution.

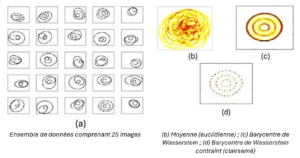

Another central challenge of modern AI is the management of complex data such as images, point clouds, and probability distributions. Welington de Oliveira is working on a key concept for these issues: optimal transport. Each piece of data is like a pile of sand. Instead of simply comparing two piles, optimal transport measures the minimum effort required to transform one pile into another, as if the sand were being moved in an optimal way.

To quantify this effort, we use the Wasserstein distance, which assesses how close or far apart two data sets are, even if they are very complex. If you have several photos of cats, optimal transport allows you to calculate an average image that best represents all of these photos. This average image, called the Wasserstein barycenter, is a kind of “composite sketch” of the cats photographed.

Thanks to the work of the CMA, it is now possible to integrate additional rules when calculating this average. For example, we can impose that only the most important information be retained (sparsity), or force the result to respect a certain structure so that it remains realistic. Thanks to powerful optimization methods, these calculations become possible even for very large data sets.

These advances make it possible to develop more robust algorithms capable of synthesizing and analyzing complex data with great precision. There are many applications: improved image processing, automatic object classification, and analysis of rare or incomplete data, such as medical images or scientific records. In short, this work helps AI to better understand the complexity of the real world, for more reliable and useful results in our daily lives.

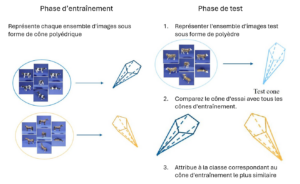

In certain fields, such as the study of rare diseases, the recognition of unique objects, or ecology, the available data is often very limited. However, traditional AI methods struggle to function effectively in these conditions, which is where Few-Shot Learning comes in, a field that involves learning from very few examples.

Valentina Sessa and her colleagues have developed an original approach to overcome this problem. Instead of representing sets of images as conventional linear spaces, they model them as convex cones, geometric structures that are better suited to capturing the diversity and variations in the data. To compare these sets, they have developed a new measure of dissimilarity based on the maximum and minimum angles between these cones.

This measure is linked to a mathematical distance called the Pompeiu-Hausdorff distance, which allows for a more refined assessment of the differences between groups of images. This method relies on non-convex optimization algorithms, designed to ensure reliable calculations even in complex situations. Thanks to this innovation, it becomes possible to better distinguish between different categories even with very few examples available.

The impact is significant: this approach improves AI performance in contexts where data is scarce, difficult or costly to obtain, such as the diagnosis of rare diseases or the identification of animal species from a few observations. It thus paves the way for more accurate and robust applications, even when the available information is limited.

This work was highlighted during the AI Workshop held in December 2025 at Mines Paris – PSL. Designed as an opportunity for internal exchange, the event allowed faculty, doctoral students, and engineers to present their projects, tools, and platforms through oral presentations and posters.

Beyond the diversity of topics, the workshop highlighted a common dynamic: building AI that is grounded in reality, capable of interacting with humans and integrating into complex systems.

Beyond technical results, CMA’s AI research shares a common ambition: to develop more reasonable artificial intelligence, in terms of the relationship between means and needs.

Faced with the race for ever larger and more energy-intensive models, mathematics offers an alternative:

This approach is fully in line with a policy of digital sobriety and responsible design, in tune with the challenges of ecological and industrial transition.

At CMA, AI is not just a technology: it is a scientific subject in its own right. By anchoring it in solid mathematical frameworks, the center’s researchers are helping to design a more reliable, understandable, and sustainable AI, an AI designed to meet the real challenges of our society.

From large language models capable of analyzing hundreds of thousands of pages to supercomputers that consume as much electricity as a small town, art...